This blog discusses ideas and concepts that I am currently thinking about for my book on Hyponoetics as an integral philosophy of mind and matter.

The Theory of Synnoesis

Synnoesis is a term I coined from Greek σύν (syn = with, together with, participating in) and νόησις (noesis = intelligence, understanding, mind, processes of thought). It represents the principle of sociality, of ethical and moral values regulating cooperative societies and communities. It also defines the structure of social organizations and the interaction within social institutions.

In my philosophy of Hyponoetics, I state that reality is not just given but is being continually shaped and created by us. The question now is: how do we – as conscious minds - shape the reality we perceive?

I assert that it is not the thinking process of an individual mind that creates and sustains the forms of reality, but the structure and organization of the individual mind in concert and unison with a community of individual minds, or what I call Synnoesis. A plurality of individual minds forms a Synnoesis or synergetic collective mind that shapes reality for those individuals. Since individual minds are an integral part of the Exocosmos (world) and are tightly coupled with its existence and phenomena, changes in Synnoesis change the exocosmic reality.

There is a hierarchy of morphic processes. Starting at the bottom, Exonoesis (Individual Mind) affects other individual minds within the same Synnoesis or across Synnoeses. A change in a Synnoesis then affects the exocosmic reality. So, a community of homogeneously thinking individuals creates its own reality, can even create new entities, such as a transcendent or personal God.

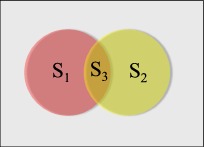

In order to better understand the concept of a community of Individual Minds, I apply set theory and Venn diagrams found in mathematics. A collective of Individual Minds that share a certain belief or a belief system constitutes a set or Synnoesis. In the diagram below, S1 = {all individuals (Exonoesis) that share belief A} and S2 = {all individuals that share belief B, but not belief A}.

The frame represents the universal set, that is, all elements that are not in S1, S2, or S3. These would be elements that are defined as "individuals", e.g. human beings, other biological organisms, inorganic and physical things.

Although a subset of S1 contains elements that are not contained in set S2 (formalized as S1 – S2 = {all individuals that share belief A but not belief B} and S2 – S1 = {all individuals that share belief B but not belief A}), some individuals may share both beliefs A and B, and therefore a new subset at the intersection of the two sets exists, S3 = S1 Ç S2. S3 is then a proper subset of S2 and S1, or S3 Ì S1 and S3 Ì S2.

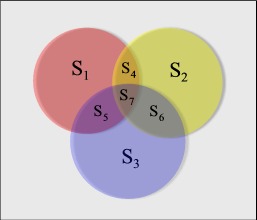

In a more complex and real-life scenario, individuals share beliefs not just with one or two synnoetic sets, but with many, each one shapes reality according to the level of participation.

An individual in subset S7, for example, shares beliefs with all other sets and subsets: S7 is the union of all elements found in S1 through S6: S7 = S1 Ù S2 Ù S3 Ù S4 Ù S5 Ù S6. Or in terms of subsets: S7 = (S1 Ç S2) Ù (S1 Ç S3) Ù (S2 Ç S3).

In set theory, the degree of participation in subsets cannot be formalized. Either an individual is an element of a subset or not. However, a synnoetic set or subset has not so much to do with containment (as in regular set theory), but with participation or involvement. Individuals share beliefs in different degrees, from fervent advocates to intriguing supporters, to fanatics. This is the positive participatory mode. Individuals, on the other hand, can also deny or be skeptical of beliefs other people share. Negation is also a form of participation.

I would like to extend current set theory and adapt it to synnoetic sets. To introduce positive and negative participatory modes, I use the following formal notations:

- Individual E1 Î S1 = {all tokens of belief A that individual E1 shares with S1}.

- Individual E1 Î S1 ¹ {all tokens of belief A that individual E1 does not share with S1 or that E1 denies or questions of S1}

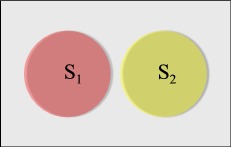

Very often, individuals don't share beliefs with other individuals. This is the case where we have two disjoint synnoetic sets.

Since individual E1 believes in A but not in B and individual E2 believes in B but not in A, communication between these antagonistic beliefs will be difficult if not impossible. They can both accept and respect each other’s beliefs but have to deny the other's belief its reality. If E1 believes in God, but E2 is an atheist, their respective realities are morphologically and ontologically different because they are both members of two disjoint synnoetic communities.

To support my thesis above, I picked two theories from the history of philosophy: Protagoras' relativism (homo mensura, from lat. homo, man and mensura, measure. "Man is the measure of all things") and Ludwig Feuerbach’s anthropologism.

The Greek sophist Protagoras is well known for his subjectivist and relativist philosophy. The relation between man and reality is subjective because man only knows about reality through his or her experience, and it is relative, in so far as each individual human being has a different view of reality and therefore no absolute or purely objective truth can be advocated.

Of all things a measure is man – of the things that are, that they are; of the things that are not, that they are not.

(Diels and Kranz, 80 B1)

This statement can be interpreted in regard to our beliefs and opinions. Our beliefs are true because we, as human beings, hold them. We are the measure of truth, and ultimately, of reality. Our beliefs "measure" reality. When we measure something, we account for an object's quantitative properties related to space, and an object's existence related to time. We apply standards in measuring the objects of our world. The standards are considered objective, but technically, they are subjective, because our mind invented those standards and methods of measure. Thus, in superimposing our mind’s metrics on reality, what we perceive and experience is essentially formed according to our mind’s measuring activity.

Protagoras gave us also an application of his homo mensura doctrine in his treatise "On the Gods":

Concerning the gods I have no means of knowing either that they exist or that they do not exist nor what sort of form they have.

(Diels and Kranz, 80 B4)

Although this statement about the existence of God is agnostic, it reflects the underlying assumption of the relativistic homo mensura theorem that our ideas and beliefs are the measure of our knowledge, that knowledge is not absolute or given, but inferred from the mind's metric ability.

In a much more lucid and systematic attempt, Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872) critically analyzed the theses of Christianity. He started with the essence of man – consciousness:

Consciousness, in the strict or proper sense, is identical with consciousness of the infinite; a limited consciousness is no consciousness; consciousness is essentially infinite in its nature.

(The Essence of Christianity, Prometheus Books, 1989, p.2)

Feuerbach thinks that man projects his or her own infinite being into objectivity and relates to this objective being as a being different from himself or herself. "God is the highest subjectivity of man abstracted from himself" [ibid, p. 31]. Therefore, religion is the relation of man to himself or herself, to his or her own nature:

The divine being is nothing else than the human being, or, rather, the human being purified, freed from the limits of the individual man, made objective – i.e., contemplated and revered as another, a distinct being. All the attributes of the divine nature are, therefore, attributes of the human nature.

(ibid, p.14)

The consciousness and knowledge of God are ultimately self-consciousness and self-knowledge. Feuerbach also speaks of "measure" when he says that "...the measure of thy God is the measure of thy understanding." [ibid, p. 29]

When it comes to the nature of faith, Feuerbach really turns theology into a form of psychological anthropology:

Thus, if I believe in a God, I have a God, i.e., faith in God is the God of man. If God is such, whatever it may be, as I believe him, what else is the nature of God than the nature of faith? ...That God is another being is only illusion, only imagination. In declaring that God is for thee, thou declarest that he is thy own being. What then is faith but the infinite self-certainty of man...?

(ibid, p.127)

Feuerbach's thesis is that God is a product of our faith, of people believing in a transcendent, personal being. God is the infinite part of our nature and mind, but projected outwards into infinity and perfection. Similarly, the world is our mind projected outwards (objects), as opposed to us (subjects) and different from us. Even how other subjects appear can be considered to be part of our mind projected outwards as another being. This does not mean, however, that I advocate a form of solipsism. I am simply stating that we can apply Feuerbach's anthropological principle to all areas of our experience, not just to God. The projective mechanism of our mind implies that. On the other hand, if we assume that Individual Minds are ultimately just one Mind and not many, then all these projections would happen within one Mind, but are perceived by the phenomenally manifested Individual Minds.

see also video The Theory of Synnoesis.